In Part One, I discussed how Peter sought to follow Jesus in a big and grandiose way, but refused to do so in a way in which Jesus actually called him to: suffering solidarity.

In Part Two, I discussed the notion of kingship in the Hebrew Scriptures and how it all comes together in the book of John. The moment Jesus is bloodied and dying is the moment where he is declared king publicly in the book, over against the cries from the Jewish leadership, “we have no king but Caesar” (John 19:15).

In this post I’d like to show how these themes came together in the early church, and from that I think we will find a word for today.

It is not uncommon in white, Protestant circles in the US to hear something like, “Jesus wasn’t political.” Or, maybe, “Christianity is about my inner life, politics have to do with my outer life.” Similarly, “church and state are separate, so I don’t think about how the two relate.”

I hope that you see how John 19 confounds such a notion. Jesus dies as a rival king. There is nothing apolitical about it. The message of John 19 is about which king the community is going to follow. Will they have no king but Jesus? Or no king but Caesar?

There is only room for one Lord.

In the first few centuries of church history, becoming a Christian had grim political ramifications. It was the church’s refusal to participate in the Roman story that got them into lots of trouble. I’ll unpack this in a moment.

I have heard time and time again Christians saying something to the effect of, “We in the US don’t experience persecution like they did in the early church. Maybe this is why nominal Christianity exists.”

This is often coupled with a vague understanding of said persecution, with the person imagining that Christians were simply put to death because they lived such holy lives, or because the Roman empire was particularly brutal. Persecution against Christians definitely occurred during the first few centuries of church history, but it is important to know why.

Christians were persecuted in the Roman Empire because they refused to adopt the Roman description of who was in charge and who deserved worship and allegiance.

They refused to allow the Roman story to take precedent over the story of Jesus.

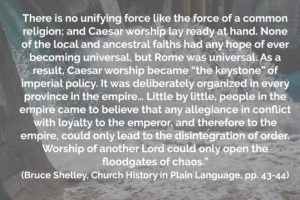

Hear how church historian Bruce Shelley describes the “keystone” of the Roman story:

We are fortunate to have documents from the early church. While all of us are likely familiar with the New Testament letters, such as Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Hebrews, and the like, there are also many letters composed shortly after those in the New Testament that have survived. These are essential pieces of literature for seeing how the early church grew and responded to various situations.

One records the martyrdom of an 86-year-old bishop, Polycarp of Smyrna (modern-day Izmir in Turkey). His death happens around 160. Hear how his exchange with the authorities went before his death:

One records the martyrdom of an 86-year-old bishop, Polycarp of Smyrna (modern-day Izmir in Turkey). His death happens around 160. Hear how his exchange with the authorities went before his death:

Therefore, when [Polycarp] was brought before him, the proconsul asked if he were Polycarp. And when he confessed that he was, the proconsul tried to persuade him to recant, saying, “Have respect for your age,” and other such things as they are accustomed to say: “Swear by the genius of Caesar, repent; say, ‘Away with the atheists!’” (Martyrdom of Polycarp 9:2; Christians were considered atheists because they did not worship the Roman gods/the emperor and the God they did worship had no image.])

“Swear the oath and I will release you; revile Christ.” Polycarp replied, “For eighty-six years I have been his servant, and he has done me no wrong. How can I blaspheme my king who saved me?” (Martyrdom of Polycarp 9:3)

Let me repeat a quote from above: “any allegiance in conflict with loyalty to the emperor, and therefore to the empire, could only lead to the disintegration of order. Worship of another Lord could only open the floodgates of chaos.”

The early church had to make a choice.

Were they going to be in league with the empire, to incorporate their story into a larger Roman story, or were they going to be a community that countered Rome’s story?

For the most part, they chose the latter, as Polycarp demonstrated above. And because they refused to participate in the annual ceremony where they would burn incense to the Caesar, they were open to being persecuted by the state. (This is also a time period when Christianity exploded in popularity, despite the dangers of associating with such a counter-cultural and nonviolent group.)

The church’s allegiance to their king, Jesus, and the ethics of the scriptural witness made them unable to pledge allegiance to Caesar and his empire.

If they would have just burned the incense—made one small concession—persecution would have never touched them (accept for some of the early and outlandish occurrences, such as Nero’s persecution). This commitment, with all of its political ramifications, was a paramount aspect of their Christian worldview. Although it seems like one small concession, in reality it would have been a compromise of their whole Christianity. Only one can be the king.

In Part Two I showed how this situation popped up in the Gospel of John and how the Jewish leadership proclaimed that they “have no king but Caesar.” The early church proudly proclaimed “we have no king but Jesus.”

Okay, now, back to the question which I hear time and time again. “Why don’t we experience persecution in the U.S.?” “Is this why there is such a prevalence of lukewarm Christianity?”

When we look at the early church, we can see a likely response. The early church was persecuted by the state because they refused to compromise their essentials and pledge allegiance to the emperor and his kingdom. They had a different ethical makeup than those in the state and lived as a counter-community. And the state reacted against them.

Is the empire reacting against you today?

If it is not, I think the early church would want you to examine the parts of your Christian worldview that bring you into conflict with the state.

- Where does the American story not line up with Jesus’ story? How can you live into that aspect of Christianity to bring you into a truer demonstration of the Christian witness in your context?

- Do you not see any aspects of Christianity that are in conflict with those in our country who hold power? If so, perhaps the early church would encourage you to examine if you have allowed the Christian story to be subsumed with your country’s story.

Here are just a few people I would recommend that you look into if you would like to see how people living as a counter-community to their state has served as a witness to Jesus’ story. I would also love if you would submit a comment with other names of people who have lived in such a manner.

- Oscar Romero

- Sister Megan Rice

- Martin Luther King Jr (see also the work of the Poor People’s Campaign today, run by Liz Theoharris and William Barber, who have both had their fair share of arrests)

And, to close, here is a word from Oscar Romero:

I will add Dorthy Day to your list. Thanks for the great article!

Thanks Melodee, Day definitely deserves to be on the list. I would love to hear from anyone else what counter-imperial prophet has been an inspiration.