During my time in ministry I had the privilege of taking a sabbatical.

Part of the time was spent in exploring the roots of my family and the roots of my theological underpinnings. Those two things took me to Scotland and to Oxford, England among other places. While in Oxford I had the opportunity to live and study, on a couple of occasions, at The Kilns – C.S. Lewis’s home in Headington Quarry just outside of Oxford proper. Those weeks were engaging, sometimes magical, sometimes disappointing, sometimes unappreciated, but overall one of the great experiences in my life.

During one stint at The Kilns, I was part of a seminar taught by a professor from the states.

We took a “field trip” one day to Cambridge to see Lewis’s ‘other’ college. On the way, we stopped at a place called The Orchard. It was an apple orchard set up with chairs and tables and tea service! It was a place where at the beginning of the 20th century the literary elites of Britain gathered to listen and write and converse. Our small group purchased tea and scones and sat in the orchard to do the same.

It was there I was exposed to the poetry of Wilfred Owen.

He was born in 1893. In 1915 he joined the Artists’ Rifles and headed to France to fight in WWI. In 1917 he was evacuated to Craiglockhart hospital in Edinburgh, Scotland (a community where a friend of mine pastored) suffering from shellshock. He spent much of his recuperation writing poetry, relating his experiences in the trenches of France. In 1918 he saw five of his poems published. He returned to France to fight that year and was killed two weeks before the Armistice that same year.

His poetry is a counter to anyone who wants to glorify or make noble or light of, war.

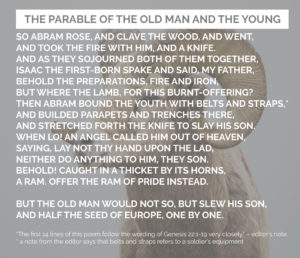

Here’s one of his poems.

This poem just smacked me in the face.

I believe that the gospel in its truest intent has political consequences. I believe that it forces us to choose between standards that are beneath what God intends and the ones that lead us to God’s kingdom. I don’t think it is partisan politics, that is I don’t think God is concerned with this technical solution or that one.

What this poem reminds me is that the great conflicts of humanity are often political but driven by more base desires. Wilfred Owen tells the story of Abram and Isaac, a story that confounds us all. The most theologians can say of it is that it is a foreshadowing of God giving us his son Jesus as the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world. Even that interpretation has its challenges to a loving and caring God. I don’t really want to dive into that here, other than to note that I know it exists.

But in using this story, he does two things.

He identifies the problem – the Ram of Pride. The angel appeals to the earthly leader to slay that Ram instead of the innocent ones. But the leader is not persuaded. And the result of unbridled pride, “but slew his son, And half the seed of Europe, one by one.”

November 15, 2018, we lost 13 members of our community in a mass murder at Borderline. We will be discussing this for years to come.

This congregation is going to invite itself to a conversation or many conversations with the community to ask what can be done.

Some will not participate, believing that the conversation is political.

Some will not participate because they believe it won’t matter.

Some will participate, honestly hoping that there is a way to curb the violence and take us a step closer to the biblical vision of a world where war and violence and weaponry are unnecessary.

What Wilfred Owen reminds me is that for all of us and our world, the enemy is Pride.

Can we set ours aside, the kind of pride that insists on being right, and listen for what might be best?

Just some more musings…

* a note from the editor says that belts and straps refers to a soldier’s equipment

Thank you.

I had not heard of this poet before, was surprised by his “ending” of the Abraham/Isaac story.

There is a challenge in speaking about war in our culture that has always seemed potentially insurmountable. I have never been able to criticize war without the perception on the part of the person/people I was speaking to/with that I was criticizing soldiers, and criticizing soldiers these days is unacceptable. Therefore, criticizing war has become unacceptable. Having never been a soldier is also a handicap in this conversation. So maybe I need to read more Wilfred Owen.

Thank you for this poem and the insight about war and pride.

Steve, you are right. It is unfortunate that people conflate a position against war, which is completely consistent with Jesus teachings, as being anti-soldier is frustrating. In an ideal world we would have no wars and no need for armies. Nations don’t often play by biblical rules and there are many unfortunate evils that we all subscribe to as nation states. One of the lessons of the Vietnam war was to understand that our soldiers need compassion and healing, not judgment. But those things are not the same as saying, “It is my prayer that no soldier need fire a weapon, or kill another human being.” These are kingdom values. And they certainly clash with the values of our present kingdom. I keep trying to figure out how to love the sinner and hate the sin. At this point I’m congruent with my literary mentor C.S. Lewis. On the flip side, his view of the necessity of war from his experiences in WWI and WWII, I’m not comfortable with, He was no pacifist. How do we hold in tension these competing values? That’s the tough place always.

Thanks for the insight!